Sculptures

CBS National News Story, early 1980s

“Collaborations with the sun are a very humbling experience.”

Rockne Krebs

Crystal Oasis for the Winter Solstice, 1982

“There is a splendid symmetry in the exhibition of works by sculptor Rockne Krebs… It begins with the way the show is arranged in perfect balance: on one side of the Corcoran’s great atrium staircase is displayed in all its richness a retrospective selection of Krebs’ drawings from 1965 through 1982, and on the other side, the artist has placed one of his spatial structures, Crystal Oasis for the Winter Solstice.

On the one side, we are able to study as never before the complex development of Krebs’ sculptural ideas and work from the time he first arrived in Washington. And on the other we are able to experience directly just what the drawings are all about. From this ideal union comes a tremendously enhanced appreciation of the hard-won clarity and depth that Krebs has been able to bring to his art.

In a way Crystal Oasis does not need such support. Like Krebs’ previous environmental structure, this one stands on its own and is magically beautiful: three crystal palm trees shining in the middle of a darkened room. But the experience is unquestionably intensified by an understanding of how the artist reached a point of such seemingly effortless mastery.

The drawings stand on their own, too, and don’t necessarily need the completion of a structural environment. Krebs’ drawings are superb, though not in a conventional sense... Jay Belloli, who organized the drawing exhibition for the Baxter Art Gallery of the California Institute of Technology, correctly states that “the drawing are by far the finest record available of the size and range of Krebs’ accomplishment as an artist.”

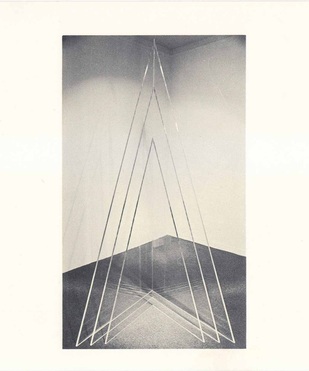

Fundamental aspects of Krebs’ early sculptures were the clarity of their geometric forms (he was influenced by the Washington Color painters, particularly by Kenneth Noland’s chevron paintings) and the degree to which they attempted to encompass and even extend the whole environment instead of standing inert in the middle of a room…

But the rapidity with which he expanded his range of interests and his artistic vocabulary remains impressive to this day. Recognizing the vast space-framing spatial potential of a new instrument – the laser, invented in the late 1950s – he conceived his first laser environment in 1967. In 1969, on the occasion of the memorable three-artist Washington show organized by Walter Hopps (Krebs, Gilliam and McGowin), he began to use sunlight as a means to structure space.

At about the same time he began to experiment with prisms as a means to the same end. In 1970 he created his first outdoor laser piece. In 1971 he first conceived the idea of using a camera obscura, on a grand scale, to expand sculptural space by projecting the outside world into the darkened rooms where his environments were installed. These exhilarating experiments and discoveries are recorded in the drawings of the time, as well as his experiments with other immaterial means of forming spaces or adding to them… All the while Krebs’ stylistic vocabulary retained a strong, linear, classical sort of severity. If there was intellectual fire at the heart of the activity, it was expressed with icy purity.

His art is quite different now, a much larger whole, and it is especially interesting to witness in the drawings the ways in which he bumped and stumbled in a tireless expenditure of creative energy to find ways to make

his sculpture say more, to incorporate autobiographical data and philosophical musings into the environmental works without spoiling their structural integrity…

The personal elements were expressed mainly in drawings and in three-dimensional pieces he titled (from his boyhood in Missouri) the “Home on the Range” series. Fantasy was one way – on paper he imagined vast, impossible structures such as a “Sun Pyramid,” and potentially fatal ones such as “Lightning Sculpture,” and brilliant, barely possible inventions such as “A Rainbow Tree.”

Humor and reverie were other means of expression: the drawings are full of puns, erotic imaginings and invented conversations with animate objects, such as the hilarious, if thoughtful, drawing whose script begins, “It began when a green pencil said to me…”

Gradually he began to bring the two sides together by learning how to deploy the full battery of his skills and tools in the larger laser environments. Among the devices he used were projecting real images upon walls by way of prisms mounted upon skylights (the huge eye in his piece for the Omni Center in Atlanta), and constructing laser housings that also functioned as independent, indoor sculptures (the “Home on the Range” construction for a cityscape laser in St. Petersburg, Fla.).

Above all this completion of Krebs’ art seems to have come from his dawning perception of the world as a unified whole to which every piece contributes – science, technology, his own artistic ego, man-made objects and the panoply of the natural world… His later works, frequently including images such as horses or trees, simply acknowledge more explicitly the ecological, spatial and symbolic possibilities.

Thus the Crystal Oasis for the Winter Solstice is indeed a fitting conclusion to the drawing exhibition, a brilliant coming together of techniques, images, structures, symbols and styles Krebs has been working out for 18 years. It expresses an aching desire to understand and to demonstrate the world’s transitory magnificence.”

Forgey, Benjamin. The Washington Post, December 24, 1983, Krebs, Crystal Clear, At the Corcoran: Brilliant

Light, Brilliant Ideas.

On the one side, we are able to study as never before the complex development of Krebs’ sculptural ideas and work from the time he first arrived in Washington. And on the other we are able to experience directly just what the drawings are all about. From this ideal union comes a tremendously enhanced appreciation of the hard-won clarity and depth that Krebs has been able to bring to his art.

In a way Crystal Oasis does not need such support. Like Krebs’ previous environmental structure, this one stands on its own and is magically beautiful: three crystal palm trees shining in the middle of a darkened room. But the experience is unquestionably intensified by an understanding of how the artist reached a point of such seemingly effortless mastery.

The drawings stand on their own, too, and don’t necessarily need the completion of a structural environment. Krebs’ drawings are superb, though not in a conventional sense... Jay Belloli, who organized the drawing exhibition for the Baxter Art Gallery of the California Institute of Technology, correctly states that “the drawing are by far the finest record available of the size and range of Krebs’ accomplishment as an artist.”

Fundamental aspects of Krebs’ early sculptures were the clarity of their geometric forms (he was influenced by the Washington Color painters, particularly by Kenneth Noland’s chevron paintings) and the degree to which they attempted to encompass and even extend the whole environment instead of standing inert in the middle of a room…

But the rapidity with which he expanded his range of interests and his artistic vocabulary remains impressive to this day. Recognizing the vast space-framing spatial potential of a new instrument – the laser, invented in the late 1950s – he conceived his first laser environment in 1967. In 1969, on the occasion of the memorable three-artist Washington show organized by Walter Hopps (Krebs, Gilliam and McGowin), he began to use sunlight as a means to structure space.

At about the same time he began to experiment with prisms as a means to the same end. In 1970 he created his first outdoor laser piece. In 1971 he first conceived the idea of using a camera obscura, on a grand scale, to expand sculptural space by projecting the outside world into the darkened rooms where his environments were installed. These exhilarating experiments and discoveries are recorded in the drawings of the time, as well as his experiments with other immaterial means of forming spaces or adding to them… All the while Krebs’ stylistic vocabulary retained a strong, linear, classical sort of severity. If there was intellectual fire at the heart of the activity, it was expressed with icy purity.

His art is quite different now, a much larger whole, and it is especially interesting to witness in the drawings the ways in which he bumped and stumbled in a tireless expenditure of creative energy to find ways to make

his sculpture say more, to incorporate autobiographical data and philosophical musings into the environmental works without spoiling their structural integrity…

The personal elements were expressed mainly in drawings and in three-dimensional pieces he titled (from his boyhood in Missouri) the “Home on the Range” series. Fantasy was one way – on paper he imagined vast, impossible structures such as a “Sun Pyramid,” and potentially fatal ones such as “Lightning Sculpture,” and brilliant, barely possible inventions such as “A Rainbow Tree.”

Humor and reverie were other means of expression: the drawings are full of puns, erotic imaginings and invented conversations with animate objects, such as the hilarious, if thoughtful, drawing whose script begins, “It began when a green pencil said to me…”

Gradually he began to bring the two sides together by learning how to deploy the full battery of his skills and tools in the larger laser environments. Among the devices he used were projecting real images upon walls by way of prisms mounted upon skylights (the huge eye in his piece for the Omni Center in Atlanta), and constructing laser housings that also functioned as independent, indoor sculptures (the “Home on the Range” construction for a cityscape laser in St. Petersburg, Fla.).

Above all this completion of Krebs’ art seems to have come from his dawning perception of the world as a unified whole to which every piece contributes – science, technology, his own artistic ego, man-made objects and the panoply of the natural world… His later works, frequently including images such as horses or trees, simply acknowledge more explicitly the ecological, spatial and symbolic possibilities.

Thus the Crystal Oasis for the Winter Solstice is indeed a fitting conclusion to the drawing exhibition, a brilliant coming together of techniques, images, structures, symbols and styles Krebs has been working out for 18 years. It expresses an aching desire to understand and to demonstrate the world’s transitory magnificence.”

Forgey, Benjamin. The Washington Post, December 24, 1983, Krebs, Crystal Clear, At the Corcoran: Brilliant

Light, Brilliant Ideas.

Rockne Krebs, 1968

Working in his Adams Morgan studio on Biltmore Street, Washington, DC

NO. XXXII, 1967

“Actual space is the medium of sculpture. A transparent object occupies space, yet it approached visual non-materiality because it can absent itself from the milieu. Paradoxically, when this occurs, perception of the space is intensified. The viewer is compelled to consciously locate and define for himself the space the sculpture occupies, even while the transparency continually confronts him with his environment. The six planes that form the interior space through which his body is moving become the armature of the sculpture.”

Rockne Krebs, 1967

Ahlander, Leslie Judd. Art in Washington 1969, 1968, published by Acropolis Books.

Rockne Krebs, 1967

Ahlander, Leslie Judd. Art in Washington 1969, 1968, published by Acropolis Books.