From the Archive: “The city at night is light” Krebs says, 1973.

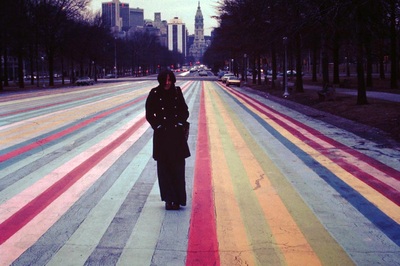

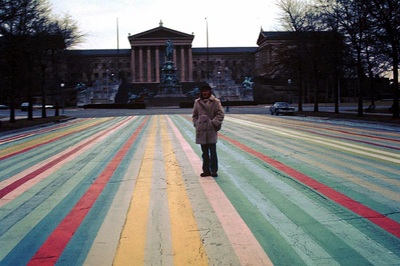

Visiting Gene Davis' Franklin's Footpath, 1972.

It was the world's largest artwork at the time.

Richard, Paul. The Washington Post, April 2007.

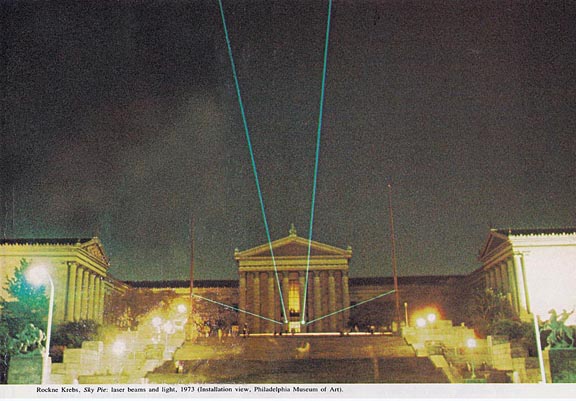

“I was working at the Philadelphia Museum of Art back in 1973, when David Katzive, the head of the Museum's Division of Education and the Urban Outreach Program, commissioned Sky Bridge Green, which was one of the most extraordinary, beautiful artworks I have ever experienced. I watched Rockne tinker with the impressively huge laser that he had set up on the east portico of the Museum to shoot a beam of light straight down the Benjamin Franklin Parkway to a mirror on Billy Penn's hat on the top of City Hall.” William F. Stapp, December 2, 2012

| Krebs originally called the piece Sky Pi, he re-titled it Sky Bridge Green, perhaps after he and David Katzive met this man admiring the laser sculpture. “An elderly man, a stranger, was standing there at City Hall gazing in astonishment at the lights that came from the museum. When Krebs and Katzive then returned to the museum, they met the man again, staring at the light above him, climbing the museum steps. 'It’s like walking into heaven,' said the stranger.” Richard, Paul. The Washington Post, 1973, The City at Night Is Light. Sky Bridge Green was a bridge to the sky hovering above Davis' Franklin’s Footpath. |

Rockne Krebs’ lasers pierce the Philadelphia air

When read from below strictly from the point of view of style, the piece was like an excessively simple sculpture somehow suspended in the sky.

Yet it was impossible to read the piece merely as a formalist tour de

force. The piece emphasized with great tact and intelligence the street pattern of the city, in this case the broad, arrow-straight line of Franklin Boulevard that leads directly from City Hall to the knoll on top of which sits the museum temple. It interacted strikingly with other man-made aspects of its environment: fountains, equestrian statues, office buildings, street lights…These relationships changed radically as one changed one’s vantage point, and in view of the enormous territory covered by the piece, these possibilities were immense…” Forgey, Benjamin. Art in America, September-October 1973, Rockne Krebs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

"Krebs, for all his precision, thinks about light like a mystic…"

How is it beautiful? How is it art? What is it, in fact, that Krebs has done? In the first place, unlike many of the unhappy couplings of art and technology… in the heady days of the mid-‘60s, Krebs’s laser environments represent a triumph of vision of over technique.

After all, the idea of making “sculpture” out of a non-material “substance” such as light is in itself an incisive bit of poetry, and when you get down to it, Krebs, for all his precision, thinks about light like a mystic…

On Franklin’s Footpath, Davis’ street painting, the trees enveloped me in almost total darkness. The laser beams seemed like everlasting comet trails – pure, inexplicable, beautiful.” Forgey, Benjamin. The Evening Star and The Washington Daily News, May 1973, A Spectacle of Light.

aging statues sprinkled through cities. They once seemed large as life, or larger, but they seem so no longer…It is the city that has killed them…where the city pushes in the monuments seem lost. Our cities are too big, too busy, all sculpture seems too small. Krebs’ work, as you might guess, is huge...It succeeds because it is not made of steel, or of bronze or plastic. It is made of light….Though weightless and insubstantial, they manage to wholly dominate their visual competition." Richard, Paul. The Washington Post, 1973, The City at Night Is Light. *This article appeared in several other newspapers around the country and abroad.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed